"I was in Italy for 18 years, and when I came back here my mission

was to get Christians to stay here," he says. "The Pope in Lebanon two

years ago had established a mission to get Christians in the East to

stay here."

Father Yako laboured among the Syriac Catholics, one

of the oldest Christian communities in the world, who had seen the

number of Christians in Iraq decline from over one million at the time

of the American invasion in 2003 to about 250,000 today. He sought to

convince people in Qaraqosh, an overwhelmingly Syriac Catholic town,

that they had a future in Iraq and should not emigrate to the US,

Australia or anywhere else that would accept them. His task was not

easy, because Iraqi Christians have been frequent victims of murder,

kidnapping and robbery.

But in the past six months Father Yako has

changed his mind, and he now believes that, after 2,000 years of

history, Christians must leave Iraq. Speaking at the entrance of a

half-built mall in the Kurdish capital Irbil where 1,650 people from

Qaraqosh have taken refuge, he said that "everything has changed since

the coming of Daesh (the Arabic acronym for Islamic State). We should

flee. There is nothing for us here." When Islamic State (Isis) fighters

captured Qaraqosh on 7 August, all the town's 50,000 or so Syriac

Catholics had to run for their lives and lost all their possessions.

Many

now huddle in dark little prefabricated rooms provided by the UN High

Commission for Refugees amid the raw concrete of the mall, crammed

together without heat or electricity. They sound as if what happened to

them is a nightmare from which they might awaken at any moment and speak

about how, only three-and-a-half months ago, they owned houses, farms

and shops, had well-paying jobs, and drove their own cars and tractors.

They hope against hope to go back, but they have heard reports that

everything in Qaraqosh has been destroyed or stolen by Isis.

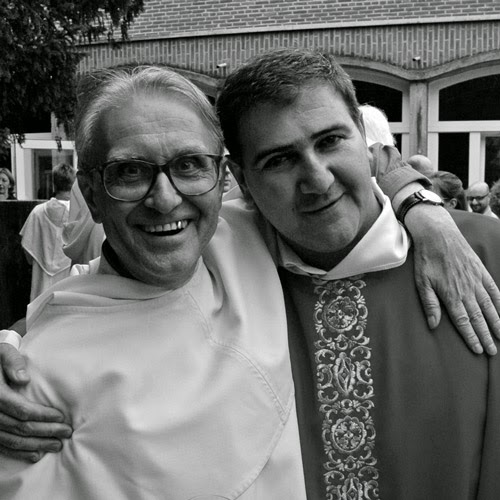

Christians who fled Mosul pray at a church in Qaraqosh

Some have suffered worse losses. On the third floor of the

shopping mall in Irbil down a dark corridor sits Aida Hanna Noeh, 43,

and her blind husband Khader Azou Abada, who was too ill to be taken out

of Qaraqosh by Aida, with their three children, in the final hours

before it was captured by Isis fighters. The family stayed in their

house for many days, and then Isis told them to assemble with others who

had failed to escape to be taken by mini-buses to Irbil. As they

entered the buses, the jihadis stripped them of any remaining money,

jewellery or documents. Aida was holding her three-and-a-half month old

baby daughter, Christina, when the little girl was seized by a burly IS

fighter who took her away. When Aida ran after him he told the mother to

get back on the bus or he would kill her. She has not seen her daughter

since.

It is not the savage violence of Isis only that has led

Father Yako to believe that Christians have no future in Iraq. He points

also to the failure of both the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan

Regional Government (KRG) to defend them against the jihadis. Christians

in Iraq have traditionally been heavily concentrated in Baghdad, Mosul

and the Nineveh Plain surrounding Mosul. But on 10 June some 1,300 Isis

fighters defeated at least 20,000 Iraqi army soldiers and federal police

and captured Mosul. The army generals fled in a helicopter. In mid-July

Christians in the city were given a choice by Isis of either converting

to Islam, paying a special tax, leaving or being executed. Almost all

Christians fled the city.

Kurdish peshmerga moved into Qaraqosh

and other towns and villages in the Nineveh Plain. They swore to defend

their inhabitants, many of whom stayed because they were reassured by

these pledges. Father Yako recalls that "before Qaraqosh was taken by

Daesh there were many slogans by the KRG saying they would fight as hard

for Qaraqosh as they would for Irbil. But when the town was attacked,

there was nobody to support us." He says that Christian society in Iraq

is still shocked by the way in which the Iraqi and Kurdish governments

failed to defend them.

Johanna Towaya, formerly a large farmer and community leader in

Qaraqosh, makes a similar point. He says that up to midnight on 6 August

the peshmerga commanders were assuring the Syriac Catholic bishop in

charge of the town that they would defend it, but hours later they fled.

Previously, they had refused to let the Christians arm themselves on

the grounds that it was unnecessary. Ibrahim Shaaba, another resident of

the town, said that he saw the Isis force that entered Qaraqosh early

in the morning of 7 August and it was modest in size, consisting of only

10 vehicles filled with fighters.

At first, IS behaved with some

moderation towards the 150 Christian families who, for one reason or

another, could not escape. But this restraint did not last; looting and

destruction became pervasive. Mr Towaya says that the Isis authorities

in Mosul started "giving documents to anybody getting married in Mosul

to enable them to go to Qaraqosh to take furniture [from abandoned

Christian homes]."

As so many had fled, there are few who can give

an account of how IS behaved in their newly captured Christian town.

But one woman, Fida Boutros Matti, got to know all too well what Isis

was like when she and her husband had to pretend to convert to Islam in

order to save their lives and those of their children, before finally

escaping. Speaking to The Independent on Sunday in a house in Irbil,

where they are now living, she explained how she and her husband Adel

and their young daughter Nevin and two younger sons, Ninos and Iwan,

twice tried to flee but were stopped by Isis fighters.

"They took our money, documents and mobile phones and sent us

home," she says. "After 13 days they knocked on our door and the men

were separated from the women. Thirty women were taken with their

children to one house and told they must convert to Islam, pay a tax or

be killed. We told them that since they had taken all our money, we

could not pay them." Four days later, some fighters burst into the house

saying they would kill the women and the children if they did not

convert.

Soon afterwards, Mrs Matti was taken to Mosul in a car

with three other women and a guard who, she recalls, threw a grenade

into a house on the way to frighten them. In Mosul they were taken first

to al-Kindi prison, formerly an army camp, but did not enter it and

then their guard got a phone call to bring them to a house in the Habba

district of the city.

In the house, she and the three other Christian women were put in

one room, next to another in which there were 30 Yazidi girls between

10 and 18 who were being repeatedly raped by the guards. Mrs Matti says

that "the Yazidi girls were so young that I worried about Nevin and told

the guards that she was eight years old though she is really 10".

They

told her that her husband, Adel, had converted to Islam. She asked to

speak to him on the phone, saying she would do whatever he did. They

spoke, and agreed that they had no choice but to convert if they wanted

to survive.

When they appeared before an Islamic court in Mosul to

register their conversion, their three children were given new, Islamic

names: Aisha, Abdel-Rahman and Mohammed. They went to live in a house

in a Sunni Muslim district and from there – here the husband and wife

are circumspect about what exactly happened – they secured a phone and

contacted relatives in Irbil. They said that they needed to take one of

their children for medical treatment in Mosul city centre, and, once

there, they had a pre-arranged meeting with a driver who took them by a

roundabout route through Kirkuk to the protection of the KRG.

The

trauma of the last six months has been overwhelming for the remaining

Christians in Iraq. The Chaldean Archbishop of Irbil, Bashar Warda,

heads an episcopal commission to help displaced Christians whom he says

number 125,000, or half the total remaining Christian population. Unlike

other displaced people in Iraq, the Christians are mostly cared for by

the churches. He says that there will always be a few Christians

remaining in Iraq, but overall "they have lost their trust in the land.

Some 80 or 90 are leaving every day for Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan."

Others would go if they had money and visas.

Mounting persecution

since 2003 and now the final calamity of Isis taking Mosul and the

Nineveh Plain has convinced many that they can no longer stay. The

archbishop suspects that, even if IS is driven back and Christians can

return to their homes, half of them will only stay long enough to sell

their property. Almost exactly a hundred years after the Armenian

Christians in Turkey were slaughtered or driven into exile, the end has

come for the Christian community of Iraq. "Have no doubt," concludes

Archbishop Warda, "that here is massacre, here is a tragedy."

Iraq’s Christian heritage

The

Christian communities in Iraq can trace their history back to the early

days of their faith. Most are Chaldeans, a small sect which is

autonomous from Rome but which recognises the authority of the Pope.

There are an estimated 500,000 ethnic Assyrians indigenous to northern

Iraq, south-east Turkey, north-east Syria and north-west Iran. This

group is so ancient that some of its members still speak Aramaic, the

language of the New Testament.

The country’s other major Christian

community is also Assyrian, and its Ancient Church of the East, having

embraced Christianity in the first century AD, is believed to be the

oldest Christian denomination in Iraq.

In addition to these

groups, there are small communities of Syrian Catholics, Armenian

Orthodox and Armenian Catholic Christians, as well as Greek Orthodox

and Greek Catholic communities.

Jamie Merrill